As everyone knows, recreational wargaming with toy soldiers (or ‘miniatures’ are they are euphemistically known)has been around for at least a couple of centuries, and arguably much longer.

It has been the rise of Warhammer, created in 1983 by Bryan Ansell, Richard Halliwell, and Rick Priestley, that has gradually brought the practice close and closer to the status of a mainstream recreational activity – and not just one played by socially-awkward pre-teen boys. Film stars and influencers now often openly admit to a fascination with painting and playing with colourful toy soldiers in the now well-developed fantasy setting.

Over a slightly longer period than this, Dungeons & Dragons has similarly come into the light in a huge resurgence both in playing and in public awareness. And again, role playing with toy soldiers is the attraction.

My wargaming with toy soldiers dates back to before D&D and before Warhammer, to the era more influenced by Don Featherstone’s 1962 book “Wargames” and published rule-sets like the Wargame Research Groups’ Ancient Wargames rules. But don’t panic – I don’t intend to go into a tedious nostalgia trip at this point.

There are still many thousands of wargamers who continue to wargame historical subjects outside the Warhammer universe, and in recent years they too have flourished (perhaps there is some synergy between the various tribes of toy soldier fans) – with many hundreds of sets of wargame rules and thousands of different miniatures in metal, resin and plastic on the market. Anyone who likes to play games with toy soldiers can pretty much play in any period in human history (from stone age to the present day) and beyond.

So what?

Every so often I get the toy soldiers out and remind myself of the pleasure they give me. Most of my gaming activity is professionally designing, writing and facilitating serious games on often very serious real-world subjects. This is stimulating and engaging and a love my work. And sometimes it can even be described as ‘fun’ (though we like to call in ‘professionally satisfying’). However, all of this creative designing of games to a specific purpose leaves little room for genuine playfulness.

And so I look for some specific things when I get the toy soldiers out which may be different to some (if perhaps not all) other wargamers.

- I’m looking for my toy soldier games to give me the opportunity to create for myself, or myself and my friends, a believable narrative. Like many forms of creative entertainment, the willing suspension of disbelief principle applies here just as much.

- If I’m playing an historical game I generally want it to reflect my reading of the history. Wargames that are just themed in an historical period, can possibly be fun, but fundamentally unrealistic and focussed only on generating a ‘fun game’ are what Paddy Griffith (founder of Wargame Developments) used to call ‘mere games’ – that is games that contain no discernable element of historical simulation.

- If I’m playing fantasy or science fiction, then I’m looking for internal logic. So many games in these genres lack that internal consistency that they to can also be described as ‘mere games’ – they can be so abstract or random that it is hard to find that important believable narrative.

- I want something easy(-ish) to play and which moves on at an entertaining pace. I spent far too long in my early game designing and wargaming life writing and wrestling with over-complex, slow moving game systems in search of ‘total realism’. Of course, as is now well understood, there is a spectrum of playability-realism (recognised officially in the MoD’s Wargaming Handbook, no less!). And for my own recreation, I’d say I’m probably around two-thirds of the way towards the ‘playability’ end of that spectrum. EDIT: As John Salt has just pointed out to me – the trope that playability and realism are in some way mutually exclusive (hence a specturnm) is also often a cover for poor or lazy game design. It is, of course perfectly posisble to have a playable and realisic wargame – and this shold be the aim of every designer of wargames. On reflection I would perhaps suggest that the spectrum perhaps is more one of deciding how much abstraction you are allowing into your game. Finding the correct balance of abstraction and complexity for the purpose of your game is, I suggest, a core element of good game design. Of course you’ll have had to decide what that purpose is, and that is a longer discussion.

- Personally I need multi-player games. Two-player adversarial wargames leave me cold. And, when you think about it you can see that creating an interesting narrative is so much easier to do so with other people jointly, which leads me on to…

- Ideally I look for a cooperative wargame. Cooperation to achieve a goal is very satisfying, possibly the most satisfying way to enjoy playing with toy soldiers. And there are those who say “…but surely war is all about winning. Adversarial play is essential so you know who won.”. To a degree – but the adversary does not need to be another person – it can be a situation, an AI, a card deck or a scenario. Or the game can be GM’d like a D&D session. So many other ways of playing wargames with toy soldiers than just two players facing each other across a table chess-like. And the growth in cooperative board games is perhaps evidence that I am not alone. Plus I don’t care who won.

My criteria for what I look for in a wargame with toy soldiers are, of course, highly personal. I recommend the reader ask themselves what they really look for in their toy soldier game and are the games they are playing really what gives them joy – or are they left feeling stressed, embarrassed or defeated by complicated, expensive games in which you are always beaten by your more experienced friend.

Elephants

For me the pachyderm in the playroom is painting toy soldiers.

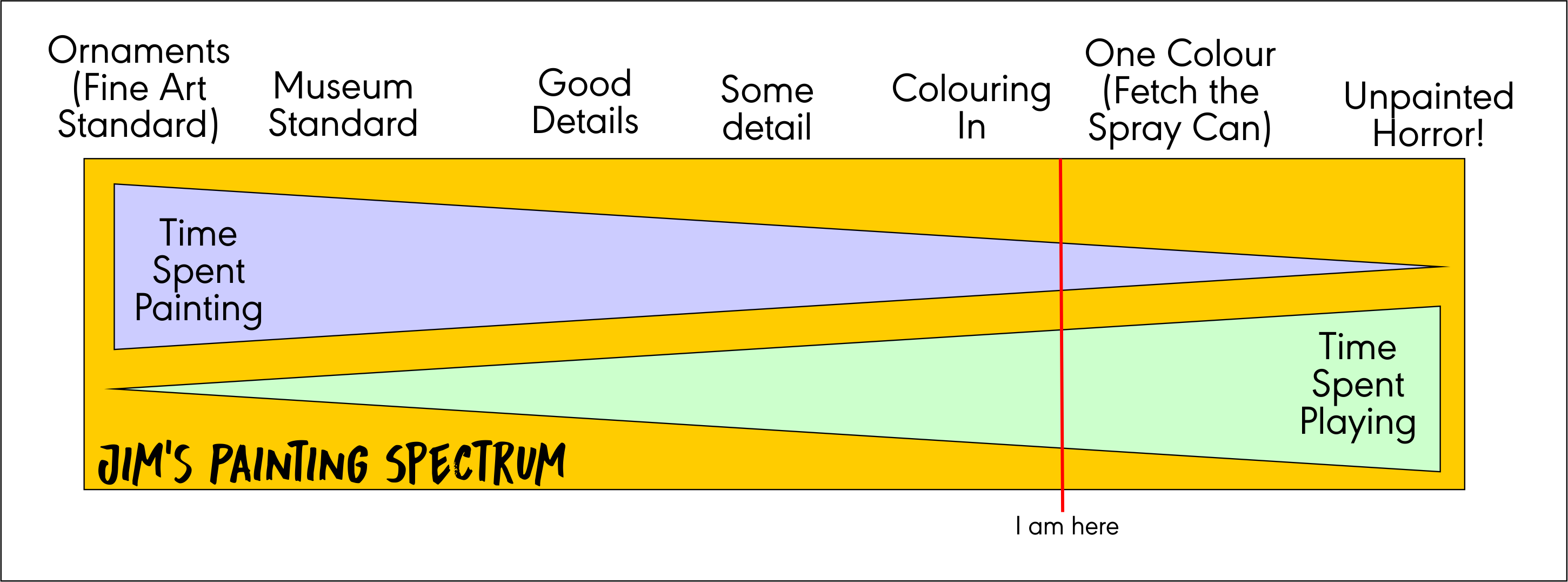

I feel that the toys are just representational markers, so painting them with loving (or even obsessive) accuracy has never been a priority. In my mind there is a toy soldier painting spectrum.

I often describe my painting technique as ‘colouring in’.

One of the things that can be discouraging, especially for newcomers, is the very high quality of toy soldier painting out there as seen in magasines or youtube videos. If you attend a wargames show like Salute in London’s docklands you will see tens of thousands of superbly painted toy soldiers. I usually find the experience dispiriting because I have neither the skill nor the patience to come even close to that standard.

However, do not be downhearted.

Those of us in the Toy Soldier Wargame Liberation Front say “Do not let those amazingly good painters oppress you with their talent and skill! Embrace the spray paint can – armies can be both Red AND Blue!”

Of course it almost goes without saying that for those of you with slightly deeper pockets and an unfulfilled desire for painted armies, ebay is your friend. Never be shamed into thinking you have to paint your own toy soldiers!

As ever, it is the game is the thing – everything else is there to help you enjoy playing and creating entertaining emerging narratives.

Do whatever works for you!

What guidelines like this must not become, in my view, is a sterile policy document created for the sake of form. It must (and in this case does) actively reflect day to day practice and be a realistic reflection of what we actually do.

What guidelines like this must not become, in my view, is a sterile policy document created for the sake of form. It must (and in this case does) actively reflect day to day practice and be a realistic reflection of what we actually do. This is often the big one. When we run a megagame there are a lot of factors in choosing a venue above its suitability for the game itself, including availability, location, access to public transport, accessibility, parking, comfort, catering space, facilities and the helpfulness of the facilities staff.

This is often the big one. When we run a megagame there are a lot of factors in choosing a venue above its suitability for the game itself, including availability, location, access to public transport, accessibility, parking, comfort, catering space, facilities and the helpfulness of the facilities staff. Running a megagame is more than just rocking up on the day with a box of components and running a game.

Running a megagame is more than just rocking up on the day with a box of components and running a game.  We all love beautiful game components, whether they are paper, card, plastic or wood. Creating and printing components is a significant cost. Ink is expensive – a colour printer ink cartridges costing £12 a shot and soon mounts up when printing large full-colour maps. Even outsourcing map printing is not necessarily cheap. AND once again its the many hours of printing, assembling, cutting, laminating etc. This all mounts up.

We all love beautiful game components, whether they are paper, card, plastic or wood. Creating and printing components is a significant cost. Ink is expensive – a colour printer ink cartridges costing £12 a shot and soon mounts up when printing large full-colour maps. Even outsourcing map printing is not necessarily cheap. AND once again its the many hours of printing, assembling, cutting, laminating etc. This all mounts up.