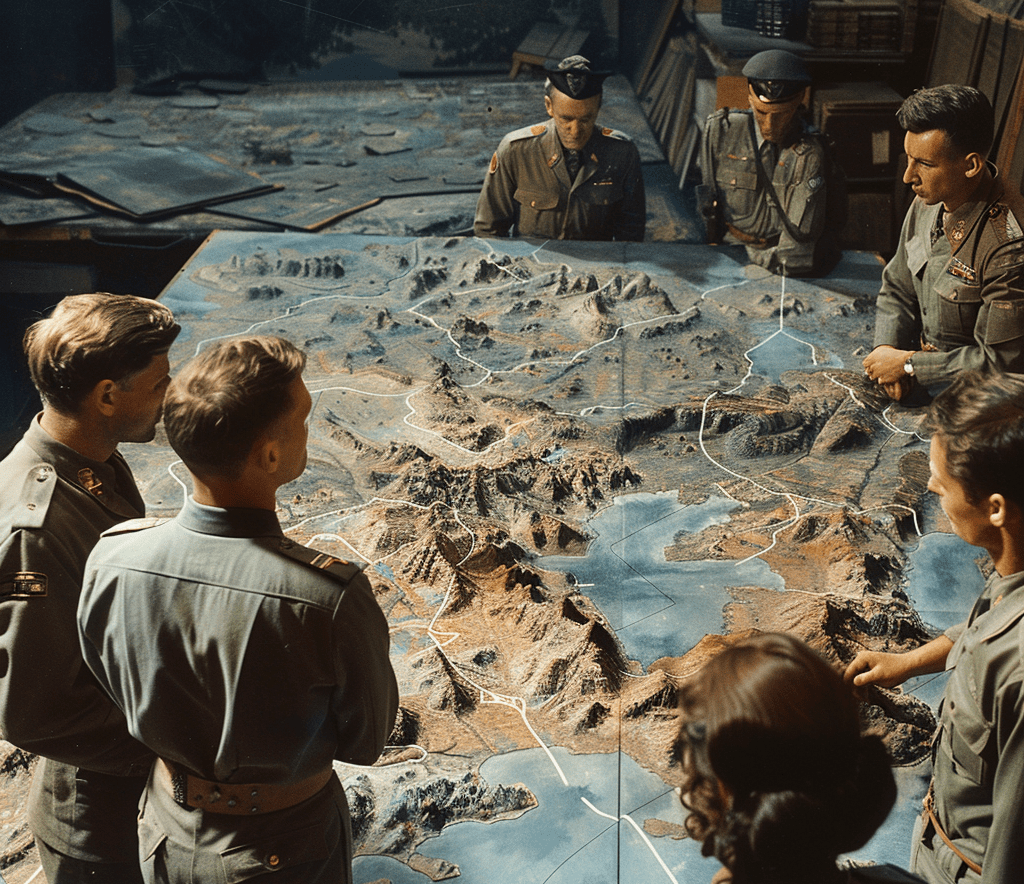

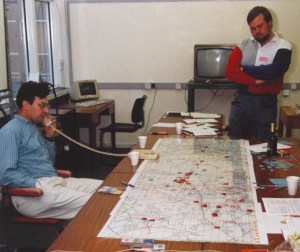

My first operational megagame was run in 1988 and was on Operation Market Garden. It was written with extensive help from Steve Hale and Graham Attfield and many hours spent in the MoD Library (then just off Whitehall). It was a pretty ambitious first project, benefiting enormously from help from Paddy Griffith who managed to get us access to the Mongomery Wing at the Army Staff College in Camberley (the Montgomery Wing was demolished sometime in the 1990s at about the same time the Army Staff college joined the joint service Defence Academy in Shrivenham).

Why Operation Market Garden?

First it was reading Cornelius Ryan’s 1974 book, ‘A Bridge Too Far’. Inspired by the huge unfolding drama of the beleaguered British paratroops at Arnhem, let down by poor intelligence and bad planning, fighting to the last bullet to hold the bridge, while at the same time a desperate, ultimately doomed, effort was being made by 30th Corps to reach them in time. This was the stuff of the war comics of my youth – who could fail to be inspired!

Secondly, inspiration came from a little known Spectrum computer game called Arnhem. My friends and I had already played the huge SPI board game Highway To The Reich, with dispiritingly over-complicated rules, unreasonable numbers of counters and requiring far too many hours to play (not to mention our disagreement with the combat resolution) – but this little, simple, game captured the problems and events of the campaign elegantly in an hour or so (it even came with a little map to track the campaign!). And it only took up 48k of memory (yes – 48k, approx 1/20th of a small photograph on your phone!). You can still play this game here.

At the same time I was increasingly involved in the new wargaming activity of megagames (see previous posts).

So the little map created the idea of a big map and counter game, even though no rules existed for such a game. There had been a couple of map and counter megagames before (most notably Andy Grainger’s Kirovograd games) – but the complexity of Operation Market Garden was going to need some bespoke solutions. The fact that no-one had done this before did not seem like a deterrent at the time.

Months of research and trying out ideas later, we discovered that this wasn’t going to be quite the simple exercise we might have first thought. Not least because it started to look like it was going to be a 100 player game!

Design Challenges

Hindsight and surprise : The campaign is very well known to wargamers and military historians, and there is always the concern that :

a. The game will not replicate the cognitive challenge of the unexpected events of the real campaign.

b. Players could fairly easily use hindsight to know a lot more about their adversary than they would have known historically.

As it turned out these were less of a problem that we first thought.

Dealing with Surprise. In the game we covered the operational surprise aspect by only allowing the Allies to write orders and not allowing the German side to write orders for the first turn of the game.

Tactical surprise was harder in that some key surprises such as that the German forces near Arnhem were stronger than anticipated would be hard to replicate. We reached the conclusion that this might be an aspect of allowable hindsight – making the battle for the Arnhem bridges less one-sided and introducing an interesting what-if dimension. i.e. “What if British 1st Airborne Division knew they were going in to a hard fight?”. The military problem remains the same, but the conduct of the battle is very different for both sides. As it happened, this was probably the only major tactical surprise that needed much thought.

Dealing with hindsight. It turned out, as we did the research, that hindsight was less of a problem than we anticipated because wargamers (and even some military historians) turn out to only have a sketchy understanding of the conduct of the campaign at the operational level. We found lots of understanding of hard-fought individual actions, dramatic episodes and broad-brush ideas of the forces involved. However, identifying all the German forces involved turned out to be a significant challenge (Helped considerably when Robert Kershaw’s absolutely excellent ‘It Never Snows In September’ came out in 1990). Many gamers and amateur historians thought they knew lots of things in hindsight, but this knowledge turned out to be insufficient to skew the progress of our game.

The second thing that challenged hindsight was that we allowed the Allies to make their own plan for Market Garden. True that all the players on the German side would know from the outset that this was a corps level thrust up a main road towards Arnhem. But the Germans at the time had also deduced that objective within a few hours. So a new Allied plan for our game meant that even though the German players broadly knew what was coming, they did not know immediately how it was going to be done.

Thirdly, as soon as players start making decisions the entire situation changes, rendering hindsight moot.

An anecdote from one of the early runs of the game illustrates this: In this game the German II SS Panzer Corps players decided not to oppose the British at Arnhem, but took time to retreat into Germany and re-enter the map with their full strength later to the east of Groesbeek, throwing their whole weight against 82nd US Airborne Division and driving them away from Nijmegen. The players in the 82nd Airborne Division’s HQ complained bitterly that this was unfair because that wasn’t what they were expecting the Germans to do. Hindsight was their undoing.

Scale

We had decided that each player team would represent a divisional HQ, with additional teams representing corps and even Army HQs, not to mention teams representing the Air Forces on each side. There were a number of reasons for this, based on earlier experience. Players like working in teams, they gain a lot from the shared experience, and it helps with managing the often confusing information they would be receiving. We had tried a system of players taking on roles is a sort of miniature ‘HQ staff’ and this had worked well.

However, this campaign has a LOT of divisions, depending on how you treat the various ad-hoc kampfgruppe of the German army, there was potentially upward of 28 teams!

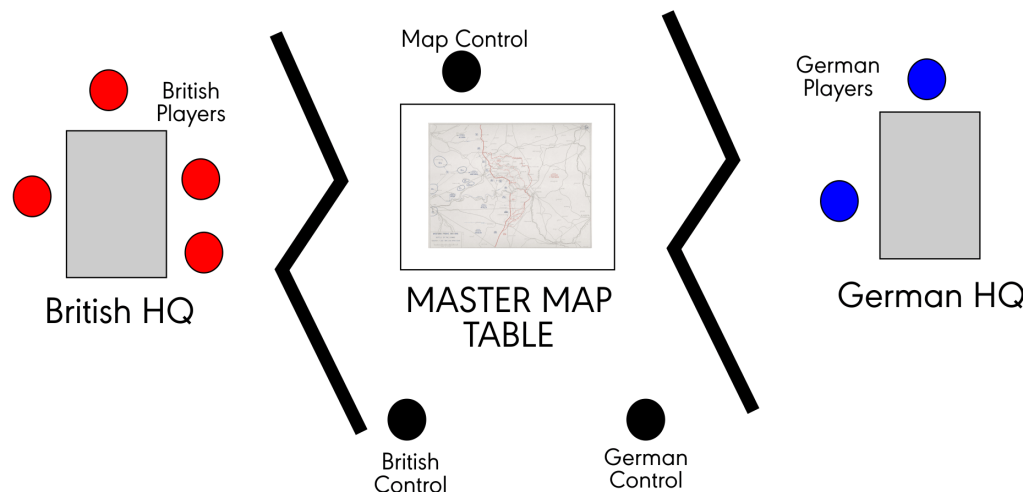

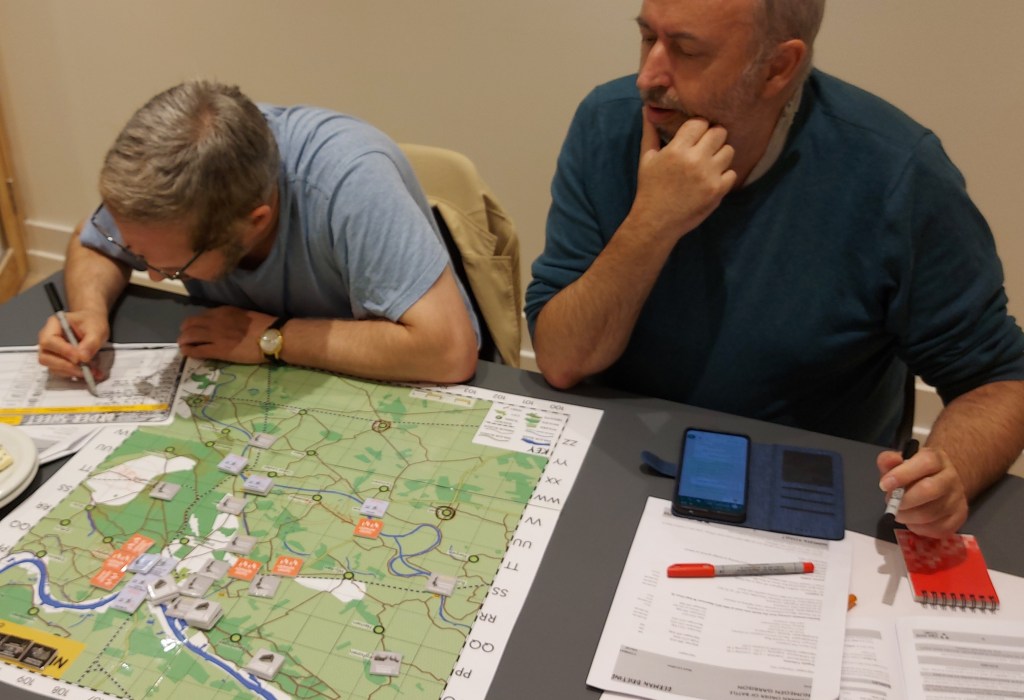

Managing this number of teams is a non-trivial problem – each team was given their own Team Control who carried their orders to the main map, and a number of other Control to coordinate the activities of the Team Controls and help keep the game moving.

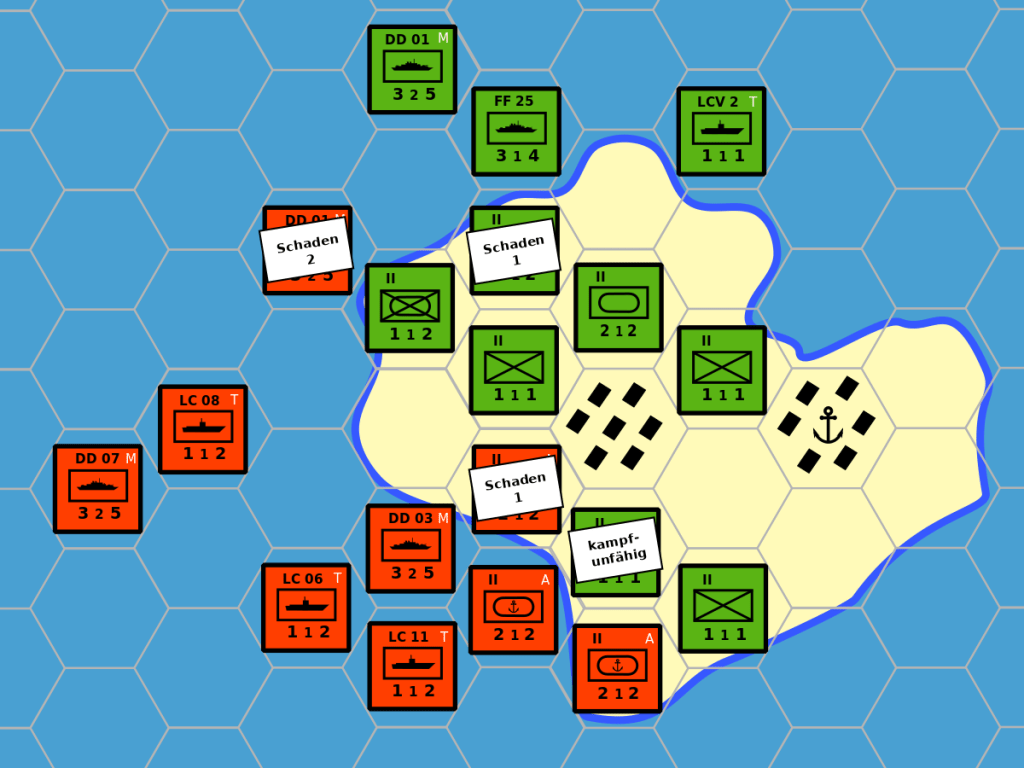

Representation

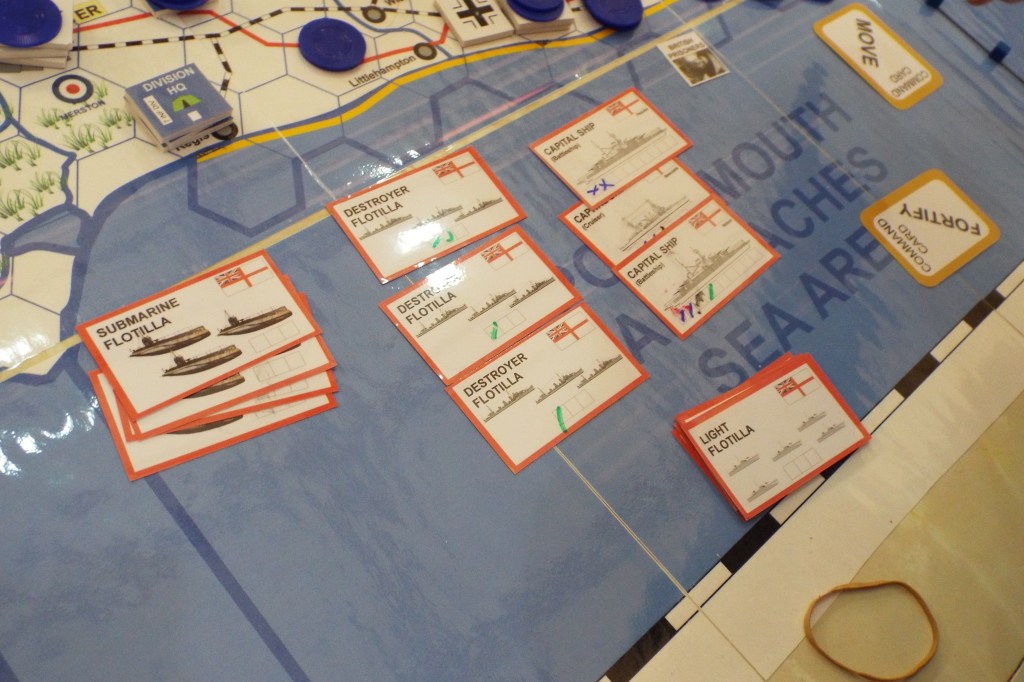

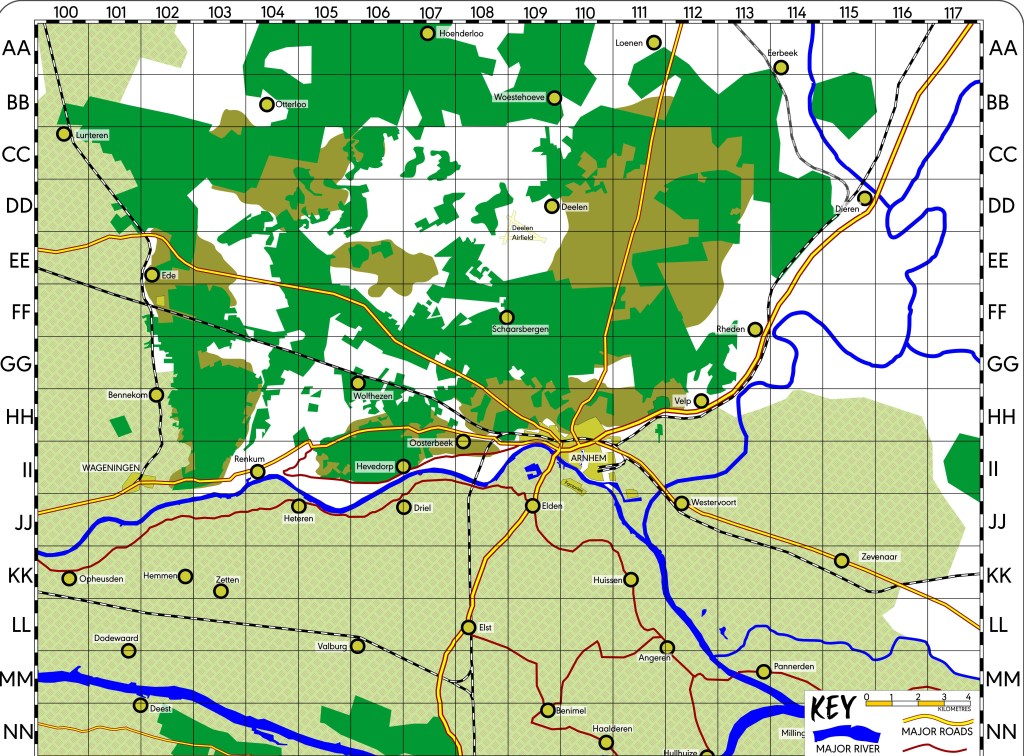

Using the 2-down principle, each Division would be issuing orders for battalions in their division – we therefore set the smallest unit represented in the game to be a battalion.

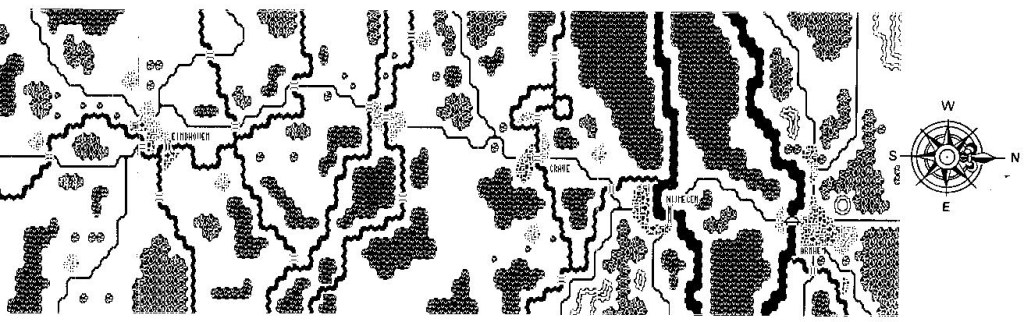

This meant a lot of players, a lot of map counters and a BIG map were going to be needed.

One of our players had access to a large plotter and they kindly generated our first map, the Control team version of which was about 5 metres long! Subsequent maps were drawn using fairly crude bitmap drawing packages of the day such as MS Paint.

We learnt a lot about producing lots of maps and counters. Control had a set of counters for their map, while players were given smaller maps covered in talcs (sheets of transparent plastic, not baby powder!) and issued with chinagraph pencils to do their own map-marking.

We discovered that even with players with previous experience on military map-marking, the quality of player-drawn map-marking left a lot to be desired! Accurate map marking of the sort practiced during the Second World War was fast becoming a lost art, even in the late 1980s and its all but gone now.

So in later versions we provided player teams with game counters to help them visualise their situation on the map.

Planning : Just One Day

For all sorts of good reasons the game had to be played in a single day. This meant the game design had to allow for enough gameplay to properly get the feel of the operation and enough ‘turns of the wheel’ for events to unfold.

Having about 6 hours of effective gameplay meant that we would be aiming to represent say, 6 days of the campaign (which is enough to find out whether the bridge at Arnhem can be taken and used). To represent the granularity of the battalion-level of operations we needed to split the day down into smaller time-slices. Initially we tried Morning – Afternoon – Night phases, but this was too difficult to do and took too long. So we have ended up with a 2-turn day, morning and afternoon, with night to be considered as an integral part of each turn.

This left us with the 30 minute turn.

Speed of adjudication therefore became our primary game design consideration because the Control Team have to read and understand players’ orders, adjudicate outcomes and report back to players and still give the players time to digest reports and write their next orders.

A tall order.

Over time the rules became more streamlined, Control Team processes better thought through – helped by giving the control team opportunities to practice in advance of the game. Even with all this we still employ a dedicated Map Control person to keep everyone on the control team strictly to time. Maintaining the intense pace of the game is a key part of the player experience too. Seeing events unfold rapidly and being under time pressure really adds to the challenge and enjoyment.

Observations, Insights and Lessons

1. Keep it as simple as possible – master the right place in the game system for abstraction. Early versions has a beautifully complex logistics system. In a bid to be ‘realistic’ we researched usage rates, loads, tonnages, transportation etc. Not only was this level of complexity too much for the players and Control to cope with in 30 minutes, but it was not necessarily much more realistic in terms of whether it evoked the right decisions and trade-offs faced by commanders at the time, at the level were were playing at. Logistics is very important in this campaign so couldn’t be ignored, but we had to move much further towards simplification of accommodate it in a way that was sufficiently realistic to be useful.

2. No Game Survives. Players will inevitably break things, either intentionally or unintentionally. If you expect this happen it makes is easier to deal with when it does. We discovered that sensitive player management was a useful skill on the Control team. We also leant a lot about calling out player behaviour when it was disruptive or inappropriate. We also learnt a lot about how to make the game material more accessible by resorting to plain English, explaining or avoiding jargon and acronyms (and my goodness there is a lot of jargon!). As game designers we often forget how much we know, especially after some deep research into a subject (“What do you mean what’s a Cab Rank – how can you not know that?”).

There are also players who are rules lawyers, pedants or nit-pickers. All of these have their place – for example sometimes a rules lawyer might usefully spot some unintended ambiguity in the rules. But sometimes these behaviours are just a player trying to ‘gain advantage by methods other than playing in-game‘ (GAMOTPiG). These methods can also include bullying and intimidation (or indeed can be a type of bullying). We’ve learnt (sometimes the hard way) that this must to be called out and shut down where it is harmful, or gently re-directed where it isn’t.

3. The ‘So What?’ Test. When creating the teams make sure there is actually a role for them. In the first games we had roles for the Dutch Resistance. Whilst the Resistance had a part to play in Market Garden it turned out that as a player role there was little agency for them in a huge multi-corps air-land battle. This can make for a dull day. So the test of team relevance is to ask yourself “what is this player (or players) going to actually DO each game turn.”.

JUST ONE ROAD

The original megagame has evolved considerably over the 37 years since the first primitive operational megagame was laid out in the Montgomery Wing. Its even been played a few times in the Netherlands.

The latest iteration of the game is called ‘Just One Road’ and is designed be a version for the connected world of the 21st Century and will be played in March 2025.

In this version, we are leveraging our more recent experience in on-line and hybrid wargaming by running the game simultaneously at a number of locations around the UK, and online, on the same day, and connected via a dedicated Discord server.

There will be three physical games, with maps and counters in Central London (representing the main ground offensive through Eindhoven), Bristol (playing the events around Nijmegen) and Nottingham (playing the battles near Arnhem). These games are held together by the High Command game (mostly corps commands, plus air forces), which is played by teams on-line.

If nothing else, this newest version with be chaotic, confusing and a huge challenge for players. What’s not to like!

For more information on JUST ONE ROAD.