One of the most interesting, and perhaps under-represented, form of recreational wargaming is the operational map wargame.

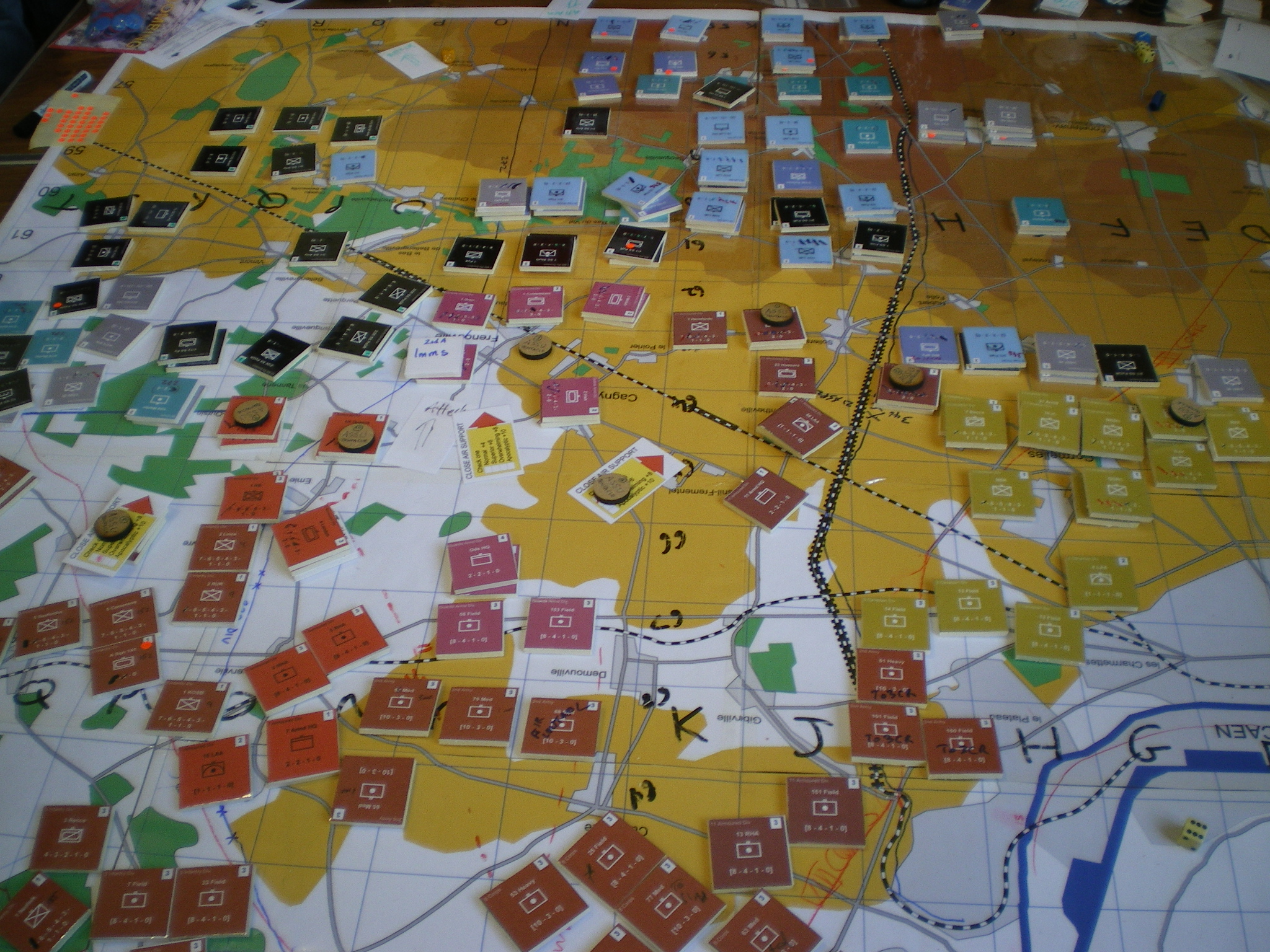

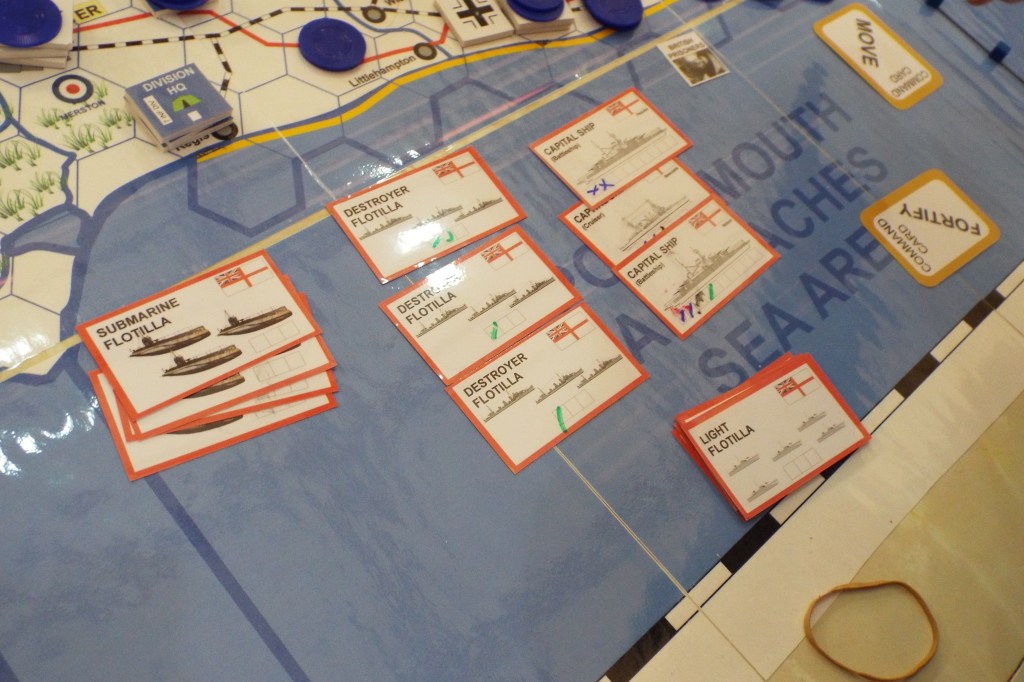

Photo : Tom Mouat

Originally migrating from the professional space to recreational gaming in the 1970s (thanks to, among others, the efforts of Dr Paddy Griffith) the notion of a wargame that did not involve lovingly painted toy soldiers was something of a radical notion. At about the same time, the Reisswitz Kriegspiel was rediscovered by recreational wargames (thanks to the efforts of Bill Leeson and Arthur Harman among others). At the same time members of the London Wargames Section were increasingly experimenting with the important concept of double blind wargames, especially for the Second World War and later periods. The double blind approach turned out to be essential for any realistic operational wargame.

Somewhat ironically, in the professional space the idea of a double blind wargame involving paper maps fell out of favour starting around the same time. Instead,computer simulation became the norm for a number of decades and adversarial wargaming itself entered something a fallow period until the early 21st century, where an appreciation of the flexibility and (importantly) low cost of manual map wargames became attractive once again. To my mind the sea-change in the acceptance of adversarial professional wargaming is marked by the official publication of the MoD’s first ever official Wargaming Handbook in 2014.

I must mention board wargames in this context. Very similar to operational map wargames in many respects, hex-map and counters board wargames have been highly successful in the recreational space since the 1960s. However, no matter how complicated, elaborate, large, small and/or imaginative these games have been they can usually be differentiated from the Operational Map Game (OMG) in a number ways:

- They generally represent the terrain of the battlespace using a highly abstracted grid system – hexagons, squares, pre-defined areas or specified ‘points’.

- They are generally open games – that is all or most of the situation is exposed to both sides in the game. Some game have ‘decoy’ counters, or other attempts to create a small element of ‘fog of war’, but it is rare to find a true double-blind board wargame.

- They are designed for relatively few participants (two is common, six or more are much less frequent).

- They are balanced so that any of the players has a chance to ‘win’, in fact rigidly deciding who won or lost in some measured way might be a defining characteristic of the genre.

- The players implement all the rules and procedures of the game themselves based on often highly detailed written instructions.

- They operate an ‘I Go – You Go’ (IGYG) structure (like simple boardgames such as draughts, ludo or monopoly).

The Operational Map Game by contrast can be characterised:

- Real maps. In the original 1970s games the maps were covered in transparent plastic (‘talc’) and units marked on using standard map symbols using chinagraph pencils. At the time this was a close analogy to how real-world military operations were planned (and how operations were conducted in the past, i.e. in the Second World War). In later years the hand-written map marking practice has become replaced by map scale-sized game counters as it was found that most recreational gamers struggle with the discipline of effective physical map-marking.

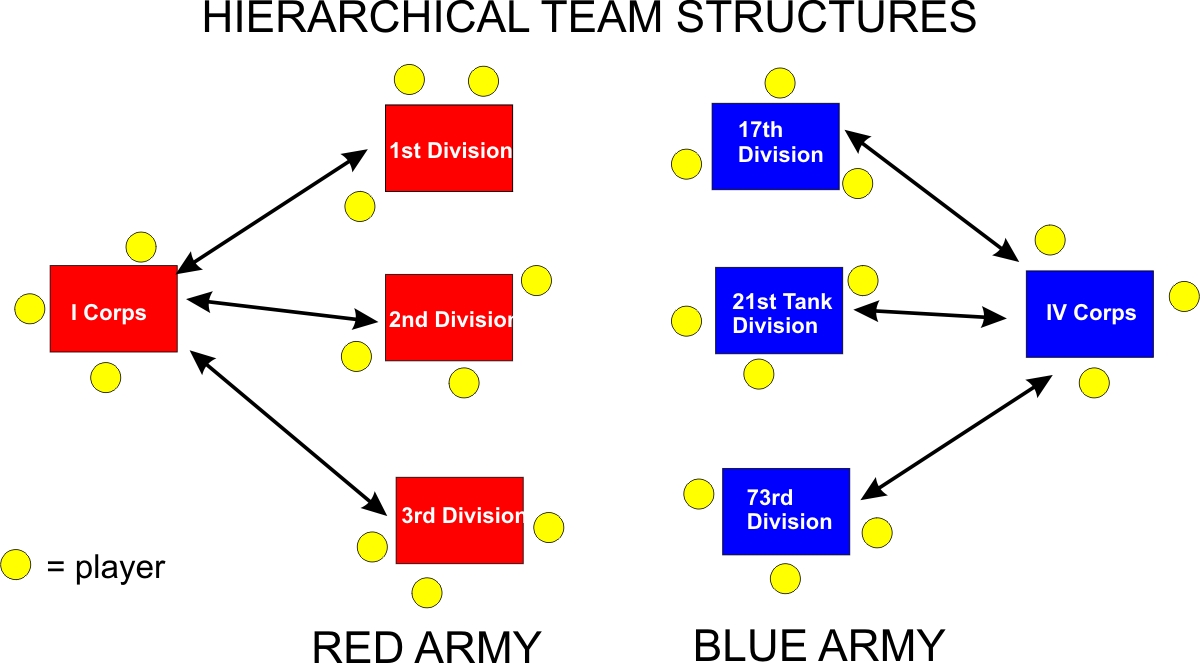

- Multiple players, often reflecting real hierarchies of command. OMGs often have multiple levels of command, and teams of players, each team replicating some aspects of a headquarters.

- Double-blind. OMGs only work properly if they are double-blind – typically the ‘three map’ model. The realistic fog of war created by this method is essential to the conduct of a successful OMG. Naturally with more player teams, the double-blind aspect is extended to knowing what friendly forces are doing as well as adversaries – thus it is common to separate out player teams representing formation on the same side and realistically restricting communication between them.

- Facilitated by a neutral Control. Often the best OMGs do not need the players to implement the rules at all and adjudication is conducted by one of more Controls. Players then concentrate on thinking about their situations, capabilities and decisions rather than how to implement game abstractions codified in the rules.

- Simulation rather than ‘winning’. Regular players of OMG tend to be less interested in an absolute sense of winning or losing, but rather on the experience of a challenging and realistic problem-set. In the recreational space these are often themed around real-world historical conflicts and players get interest and enjoyment from measuring their performance against that of their historical prototypes. An added bonus is that realistic asymmetric historical or real-world game scenarios are eminently playable without needing to arbitrary and often unrealistic ‘game balance’.

- Social interaction. Because it involves teams working together to achieve a common goal, there is a lot of camaraderie among players, as well as respect for their opponents. At the end of OMG there is always a debrief phase where both sides get to chat and see how the wargame went from ’the other side of the hill’. Often these debriefs are entertaining (or even educational) as Control reveals what was really going on.

- Simultaneous play. In OMG the action in each turn is simultaneous – they do not need to work on an ‘I Go – You Go’ (IGYG) structure because they are closed games and each side not only doesn’t know what the other side are doing, but also do not have to wait while the adversary deliberates on their ‘move’. Unlike the IGYG structure, this enables teams to get inside their opponent’s ‘OODA loop’ and simulates reality where the enemy does not wait for your ‘go’ to finish.

OMG Structure

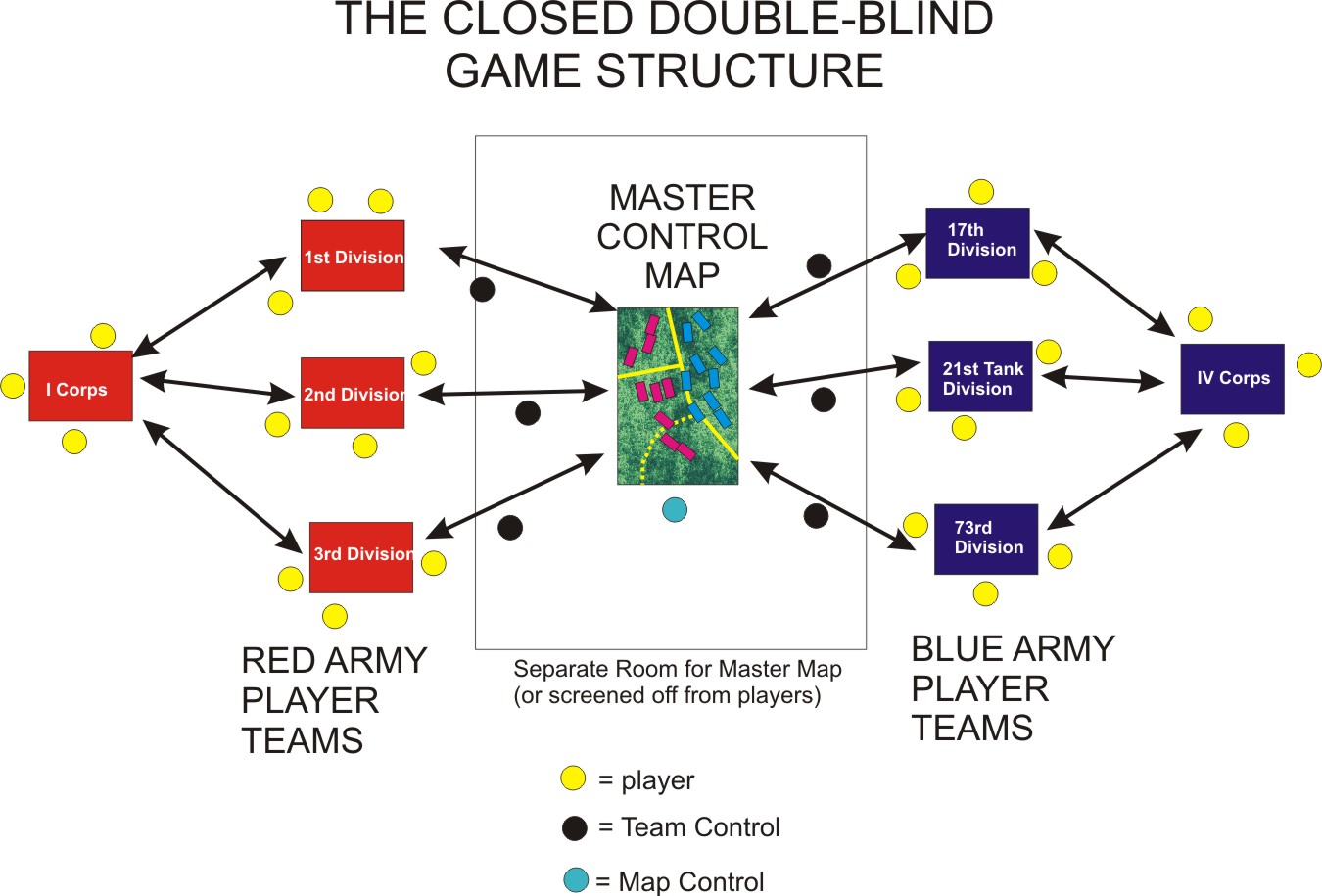

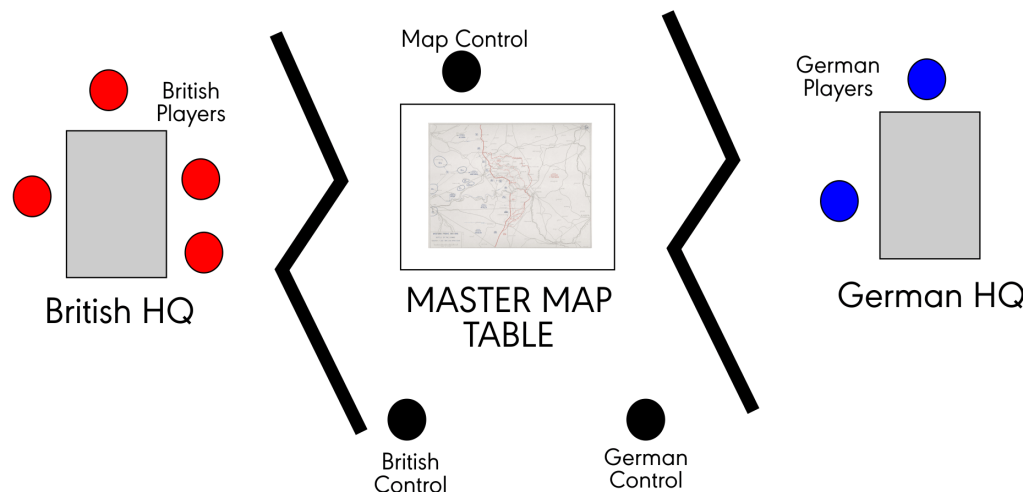

In its simplest form the classic ‘three room game’ (which is the main structure of OMGs) looks something like this:

The two sides have their own space with maps and a member of the Control team (known as Team Control) facilitating them. In the middle is the Master Map with Control adjudicators (known as Map Control).

Each player team maintains their own map, and updates it based on reports received from Control This might be brought to them by their Team Control, or transmitted via messaging systems from Map Control (or, indeed, a combination of the two).

Player teams submit orders (typically in a brief written form) to Control which then uses them, and the game rules & procedures to update the status and positioning of units on the main map, and create a narrative of events to report back to the player teams.

This basic structure works very well for two sides, and can easily be expanded for more complex operations involving multiple formations on each side. And separate rooms are not an absolute necessity, so long as the teams cannot see the master map and do not overlook or overheard their adversaries. In some of the simplest games placing players seated with their backs to the master map can suffice!

Time

In order to create genuine tension and simulate real-life frictions, the OMG only allows players a fixed amount of time to communication, discussion and to decide on and issue orders. A game with unlimited time for players to decide on their actions quickly comes to a halt and becomes deeply boring for most of the participants. The pace of an OMG has to be fairly finely judged depending on the complexity of the situation and the amount of intercommunication player teams need to do. We have found that 20 minutes is the minimum practical time, and around an hour the maximum. In that time, adjudication must be as rapid as possible and should not take up more than an absolute maximum of about a third of the time allocated to a turn, to give player the best chance of having time to think about their actions, communicate and write their orders.

Communication

In a typical multi-team OMG players communicate between teams to share information and coordinate plans and operations. This can be one of the most challenging and entertaining parts, and in some games the game rules impose limits on how much, or in what form, this communication happens. In an historical period prior to the invention of radio this might be only via written notes. In era where more advanced technology is available teams might use means such as Discord or Zoom to simulate real-world communication.

Orders

Whilst it would be easy for players to simply tell Control what they intend to do the OMG works best with written orders. These are necessarily simplified when compared with the process of writing real-world military orders, but capture the flavour of order writing. We tend to use standard proformas to help players to include all the information Map Control will need to adjudicate and update the master map consistently. Ideally this needs to reflect, even in abstract form, information that is relevent to the context. So in an historical game guide players with options that reflect the operational practice of the period, and avoid anachronism.

Adjudication & Reporting

Speed of adjudication. As mentioned above, map adjudication must be both accurate and speedy. Nothing de-motivates players more than sending in their orders then waiting for an hour of relative inactivity to find out what happed, while the Control team are in huddle elsewhere around the master map apparently enjoying their own private game.

There is a clear balance here between detail and speed – and whatever rules & procedures you use these must be measured against actual in-game processing. A common elephant trap in this regard is the game designer underestimating time needed for their Control team to master a system that seems perfectly easy to the person who designed it. Everything takes longer than you think. If you have allowed, say 10 minutes fr adjudication, your rules and & procedures should be designed to take only five minutes (or even less) to process.

In my experience adapting game systems designed for face to face play (for example from a board wargame) is likely to be inappropriately slow. In most cases it is best to use something specifically designed for OMGs.

Rigid versus free adjudication. There are considerable advantages to having a consistent, codified set of rules & procedures for your game. Not least because it allows multiple Controls to assist with adjudication. However, there are times when ‘free adjudication’ can usefully be used, especially when your Control team includes experienced subject matter experts. Often the abstracted system your used needs to be very granular and situation might arise that are not well represented by the rules. In this case Control can make a judgement on the outcome without reference to any rules. Whilst it is entirely possible to run all the adjudication in this way (with the right control team), and might seem an easy option I do not recommend it as it can be harder to maintain consistency ad is dependent on the credibility and expertise of the Control team.

Black box adjudication. In the standard OMG the adjudication process is entirely in a ‘black box’ in that the players are not given the entirety adjudication rules. We generally give them information on the underlying assumptions in those rules. So we might say “Tanks have an advantage over infantry in open country” but not “Tanks get +4 in combat resolution when fighting infantry in the open”. Interestingly I have observed that players often ascribe considerable subtlety to the results that might actually not be part of the adjudication process – post-hoc rationalisation being a significant human behavioural trait. “Ah yes, the enemy’s action must have failed because T34 tanks can’t fire their guns to their rear”.

Creating a believable narrative. Whatever system of adjudication you use they primary output is to create a credible narrative of events generated by the game. If players cease their willing suspension of disbelief then Control (or the game system) risks becoming an adversary rather than the other played teams. We teach Team Controls to report in the form of a narrative report describing in general terms the following things:

- Achievement of their intent (as expressed in their game orders)

- Status and position of their own units. This might not be completely accurate. However they would very likely know if the unit has taken heavy or light casualties

- Current Capability of their own units. An assessment of the unit’s ability to do more actions – is it exhausted or can it press on, for example.

- What they would reasonably know about the enemy their units are facing. In some cases there would be obvious clues – for example if the enemy have tanks then that would be reported. Or if the enemy was using artillery… and so on.

The reports would never be expressed in game-type metrics. So Team Control would never say “7th Battalion has lost 3 strength points and now has a combat factor of 2”. This might instead be expressed as “7th Battalion has taken significant losses and is not confident in its ability to continue the attack”

The important thing here is that the players feel they are immersed in the experience of commanding their units in the game. If they don’t believe that the results make sense, or seem arbitrary and inconsistent then this needs to be quickly corrected by Control, ideally by providing more information. Often the problem arises because some vital piece of information has been omitted (“You didn’t tell us that 12th Brigade has run out of supplies! That explains why the attack failed”). Of course errors or omissions by Control can be explained away as ‘fog of war’ or communications breakdowns, but this excuse should not be used too often.

Debriefing & Feedback

Allowing time for a plenary session at the end of the game is essential for creating opportunities for players’ stories to be heard. Quite apart from any simulation aspects, these wargames are, above all, anecdote generators, and player derive much of the pleasure of the experience in recounting that experience.

PHOTO : Tom Mouat

The other aspect of the post-game debrief is giving the players a chance to ‘peep behind the curtain’ and see the master map and get a sense of the actual situation, kept form them for most of the game. Allow this chance to just go and look at the master map.

The other opportunity the post-game debriefing session provides is the opportunity for the game designer and control team to hear player feedback on the game as an experience. This is a place for the organisers to listen to players’ feedback. I always advise that the organisers just listen and take note of what comes up and at all costs avoid becoming defensive when criticism comes up from the players – whether or not you agree or feel their comments are fair. Being defensive isn’t necessary and isn’t a good look for an event that is, after all, fun and about the player experience.

To Summarise…

So, Operational Map Wargaming (OMG) offers a immersive style of play that emphasises a good degree of realism, teamwork, and historical simulation. OMGs are distinguished by their use of real maps, multiple layers of command, and reliance on Control teams for rule adjudication, keeping players focused on strategy. OMGs foster a challenging simulation that minimises the pursuit of winning in favour of creating an authentic experience, often involving real-world scenarios. With a focus on simultaneous, rather than turn-based, play, OMGs allow teams to coordinate and communicate under time constraints, mirroring real-world military pressures. The structured adjudication, communication challenges, and immersive narrative make OMGs a rewarding, (and sometimes educational) experience, blending teamwork, camaraderie with the challenge of operational command.