A subject that has been interesting me in recent months has been how to wargame military deception effectively in the professional wargaming setting. I thought it might be useful to expose my thinking and, hopefully get feedback.

Military Deception is being used here in the sense of ‘deliberate measures to mislead targeted decision-makers into behaving in a manner advantageous to the commander’s objectives’.1

Wargaming being defined as ‘A scenario-based warfare model in which the outcome and sequence of events affect, and are affected by, the decisions made by the players’2

Wargaming will be used here to mean professional wargames developed with a serious intent, primarily in order to develop insights, conduct research or hone operational skills and conducted with participants with a professional interest in the conduct and outcome of the wargame.

Whilst games for an education or training purpose would also qualify I am not going to consider those here. Similarly I am excluding recreational wargames (thought there is no doubt overlap in all of these cases).

Approaches to Wargaming

There is a widespread popular understanding that ‘deception’ includes lying, cheating or otherwise bamboozling the other players in your game. There are many games and shows in popular culture that hold the ‘traitor mechanic’ as core part of their interactions of the participants3.

However, whilst dishonest or traitorous behaviour in recreational games might be shoe-horned into the definition of Military Deception above, I argue that this is too simplistic. In addition there is, conceptually at least, a significant difference between military deception and ‘perfidy’4. That is not to say that real-world adversaries might not act in way contrary to international conventions, and this has to be taken into account at some stage. At present I’m looking at how, within existing wargames military deception, as described in current NATO doctrine, can be usefully applied to wargames.

In the professional wargaming context there are a number strands of activity where deception plays its part and which we might usefully include in wargames:

a. Playing the Player. Game activities that are designed to deceive the players in the opposing team in a wargame.

b. Replicating Deception Effects. Game rules and procedures that model the application and effect of military deception on elements in the game not represented by players (Non-Played Elements).

c. Meta-Deception. Where the game structure and design itself deceives the players in order to achieve an effect. (for example ‘disguised scenarios’). Sometimes this happens by ‘accident’5.

Playing the Player

The cut and thrust of adversarial wargaming enables gameplay that includes aspect of deception. However the object of this deception is the enemy ‘commander’ – i.e. another player in the game. That player may or may not be personally known to their enemy, but they are often part of the same organisation, society or culture. And as such they may well be far better understood than many real-life adversaries.

Successful deception of a played adversary in our wargame runs the risk of:

a. Telling us nothing about how applying deception doctrine might work against a real adversary from a different cultural environment.

b. Becoming merely a ‘game’ of outwitting the other player – especially if that player is known to you. “Ha! I really fooled Charles this time!”. Or, worse, hold back on deception activity so as not to embarrass the adversary player who might be more senior.

c. Because of a. and b. above insights may be deeply flawed, especially in the context of a wargame designed to generate insights or conduct research.

d. Data capture is fraught with difficulty because in order to establish the effectiveness of deception the players who may have been deceived have to admit to having been deceived. Human nature being what it is (especially in hierarchical organisations) there may be a reluctance to admit to weakness or failure – even in the ‘safe to fail’ environment of a wargame.

It is entirely possible, and possibly useful, to conduct wargames where the deception activity is focussed on deceiving the enemy players. However, there is nothing special about such a wargame – it requires nothing more, structurally, than any other wargame. The main change are the decisions of the players and their ability to use military deception doctrine successfully in the their planning an execution of those plans.

Replicating Deception Effects

This is an area where there is significant opportunity for development of new models, methods and tools (MMT).

There are already many MMT to describe and adjudicate the effect of weapons and military units and, increasingly, ‘soft’ factors like information & influence operations and will to fight.

The task here is to develop game systems to enable a wargame to show the effects of military deception on Non-Played Entities (NPE).

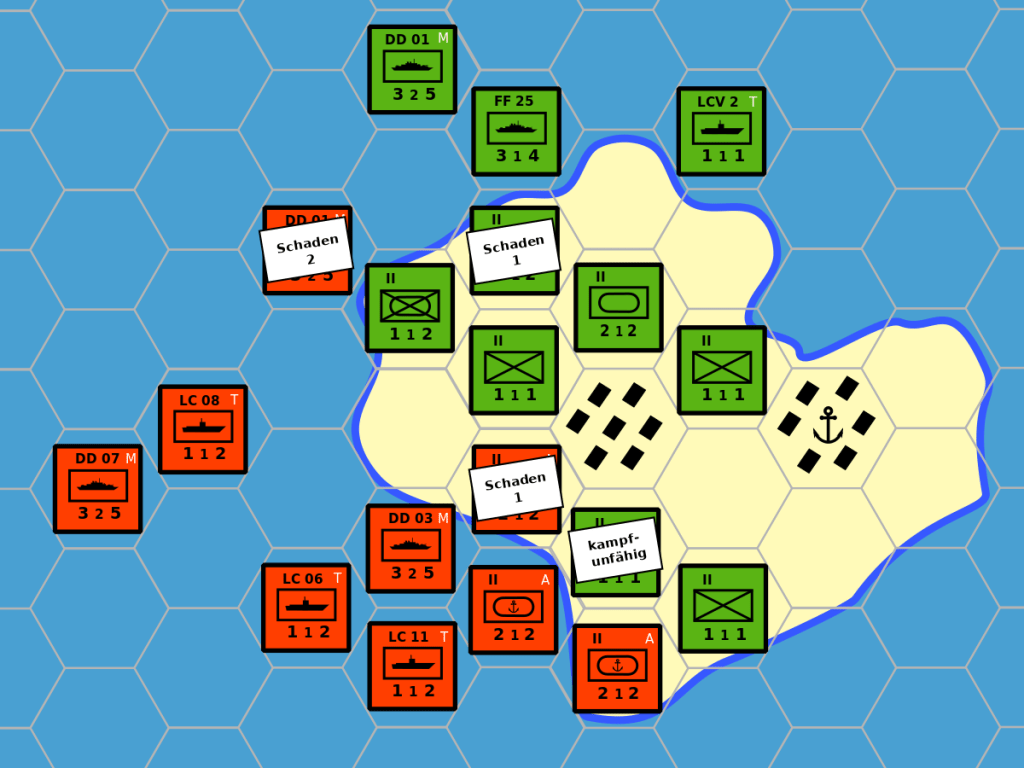

For example the smallest NPE in a map and counter wargame might be a game counter representing a battalion. When that game counter moves to attack an enemy counter we make a set of assumptions about how that battalion will fight – and these are baked into metrics of unit capability and effectiveness. These factors are then applied using the game rules and procedures to determine probability of success.

Within the model of the capability of the game counter will be assumptions about how well led it is and what tactical decisions the imaginary battalion commander is taking – these are all well below the resolution of the game, but conceptually they are factors taken into account in building the wargame orders of battle and unit statistics.

Any reflection of military deception at this level requires us to have a model of the process of deception. Military deception does not include operations security (OPSEC)6 – here we are concerned with what one might term ‘Active Deception’ as distinct from ‘hiding’.

There are many actions our imaginary battalion commander (in charge of a little game counter) might be taking at the tactical level to implement a deception plan. We are not interested in these (in the same way that we are not interested in how they might be deploying their companies or tasking their mortar platoon) – what we might be interested in is:

a. How capable is the battalion commander at employing military deception (e.g. have they read and practised their deception doctrine), and how imaginative / flexible are they?. This may be a wider question about how well trained the army they are part of is, as distinct from profiling all the tiny commanders of each game counter.

b. Are there realistic opportunities to use deception? The circumstances and environment might not be conducive to military deception. This might be something to do with terrain, or the orders the unit has been given, or the time available to develop a deception activity (these often take time to prepare and implement in real life).

c. The enemy gets a vote. Unlike kinetic fires, which have a generally consistent effect on any enemy unit in similar situations, the effect of deception is on the enemy commander. This means that it doesn’t matter how carefully crafted our tiny commander’s deception activity is, the unit commander they are facing might still not be fooled. Perhaps every counter is given a gullibility rating? But of course the gullibility of an adversary is entirely unpredictable. Behavioural science can give us considerable insights into this in building our model of ‘deceptive interactions’.

d. Finally, identifying the effects of deception. Does successful deception just mean “plus one” to the combat result, or are there other, more qualitative, effects? It is important to consider how deception changes behaviours and how this is reflected in our model.

This approach – building a model of how military deception activity might operate at the low level yields some interesting potential MMT that can be written into existing game rules and procedures so that deception is integrated into conventional wargaming seamlessly.

Especially interesting for me is the question of how does successful military deception manifest at each level? It may well be that the application of deception at battalion level might look qualitatively different to it being applied at brigade or even divisional level (where brigade or division is your level of a non-played entity).

Meta Deception

I don’t propose to discuss this in any detail, especially as Stephen Downs-Martin has written extensively and convincingly on the subject of malign wargaming in the professional space.

However, there is potentially a place for disguised scenarios as a tool for developing insights without players using ‘20/20 Hindsight’ and approaching subjects under examination with fresh eyes. Whilst strictly speaking this fall outside military deception doctrinally, the principles of deception, if applied consciously and in a rigorous way, can be applied to test players intellectually and generate insights – though care must be taken to use deception in this context that it does not pre-load the decisions of the players to force particular insights.

Ultimately the aim of any wargame must be to open out thinking in new directions and encourage meaningful insights.

Footnotes

1 Allied Joint Publication, AJP-3.10.2, Edition A, Version 2, ALLIED JOINT DOCTRINE FOR OPERATIONS SECURITY AND DECEPTION

3 2021 ‘De Verraders’ on Dutch TV channel RTL4 or 2008 ‘Battlestar Galactica: The Board Game’ created by Corey Konieczka

4 Perfidy is understood as deception that falls outside the provisions of international Laws of Armed Conflict such as the Geneva Convention 1949.

5 ‘Preference Reversal Effects and Wargaming’, Stephen Downes-Martin 2020

6 OPSEC is defined as: ‘the process that gives a military operation or exercise appropriate security, using passive or active means, to deny an adversary knowledge of the essential elements of friendly information, or indicators of them’ (AJP 3.10.2)